This year of 2019 is the 100thanniversary of the “Black Sox” scandal. This article comes from the Frommer vault

On July 16, 1889, Joseph Jefferson Wofford Jackson was born into a poor family in Greenville, South Carolina. He never learned to read or write. By the time he was six years old, he worked as a cleanup boy in the cotton mills.

By age 13, he labored amidst the din and dust a dozen hours a day along with his father and brother. It was hard and back-breaking employment. Playing baseball on a grassy field was his way of escape. It was there where Joe’s natural ability stood out. Baseball was his game, and he loved it. The youth had such passion and skill that he was recruited to play for the mill team organized by the company.

One humid and hot summer day, Jackson was playing the outfield. His shoes pinched. He removed them and played in his stocking feet. An enterprising sportswriter gave him the nickname: “Shoeless Joe.” Even though it was reported that was the only time Jackson ever played that way in a game—the “Shoeless” moniker stuck. He hated the name, feeling it cruelly referenced the fact that he could not read or write.

From the mill team, Jackson moved on to play with the Greenville, South Carolina Spinners. It was there in 1908 that a scout recommended him to Philadelphia Athletics owner/manager Connie Mack, who purchased his contract for $325.

The youngster made his Major League Baseball debut on August 25, 1908. The more he played the more his potential impressed everyone. An article in the Evening Times noted: “He has justified early predictions of his abilities. With experience and the coaching of Manager Mack, he should turn out to be…the find of the season.”

Sadly, Jackson was unable to read what the Philadelphia newspaper wrote about him. He could not even read menus. In restaurants, he usually ordered what another player did. Sadly, he did not fit in with his teammates or the big city. Homesick, he jumped the team and took a train back home.

Mack sent Jackson down to a minor league team in Georgia in 1909, where he won the batting title. In 1910, Mack called him up to the big league team but decided that Jackson lacked the disposition to play in a big city like Philly. In one of the worst trades in baseball history, the 6’1”, 190-pound Jackson was shipped to Cleveland for a player named Bris Lord (Bristol Robotham Lord, nicknamed “The Human Eyeball”) and $6,000.

Shoeless Joe fit in quite nicely in Cleveland, where he batted .408 in 1911. In mid-season of 1915, after compiling a .375 career batting average with the Ohio team, Jackson was traded for three players and $15,000 to the White Sox.

It was in Chicago that Jackson made a point of wearing alligator and patent-leather shoes—the more expensive the better. It was as if he were announcing to the world, “I am not a Shoeless Joe. I do wear shoes. And they cost a lot of money!”

With the White Sox, Jackson became one of baseball’s storied stars. His defensive play was at such a remarkable level that his glove was called “the place where triples go to die.”

On offense, he was one of the most feared hitters of his time. Babe Ruth copied his swing, claiming Jackson was the greatest hitter he ever saw.

Then along came 1919!

The 1919 Chicago White Sox were one of the greatest teams of their era. Paced by Jackson who batted .351, they won the American League pennant. They were 3-1 favorites to win the World Series as they prepared to face off against the Cincinnati Reds.

Prior to the series, betting odds started to shift to even money. The word on the street was that New York gambler Arnold Rothstein was behind the swing and that the series was fixed.

Hearing the rumor, the 31-year-old Jackson asked Chicago manager Kid Gleason and owner Charles Comiskey to bench him. But they insisted he plays. They would have been crazy to put down their best player.

During the series, Jackson hit the only home run. He posted the highest batting average. He committed no errors. He established a new World Series record with 12 hits. Nevertheless, the Reds won the Fall Classic.

Edd Rousch, who played for the Reds, insisted that charges that the series was fixed was nonsense. “We were just the better team,” he said.

“Maybe I’m a dope but everything seemed okay to me,” said umpire Billy Evans, who worked the series.

But the rumor of a fix persisted as the 1920 season got underway. The White Sox were driving hard to their second straight pennant when a petty gambler in Philadelphia broke the news that a Cubs-Phillies game had been fixed in 1919.

That led to a gambling investigation—its focus the 1919 World Series. With only a couple of days left in the 1920 season, a Grand Jury was called to determine whether eight White Sox players should stand trial for allegedly throwing the 1919 World Series. Jackson was one of the eight players.

It took the jury a single ballot to acquit all eight accused players. Incredibly, the very next day, baseball’s first commissioner—Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who came to power in the fall of 1920 with a lifetime contract and a mandate to clean up the game using whatever methods he saw fit—banned all eight players from baseball for life. The bigoted Landis was brought into organized baseball with a reputation of being a vindictive judge, a hanging judge.

He was all of that.

Was there a plan to throw the World Series in 1919? Was a plan carried out? If so, which games were dumped? What role did each banned player have? Why was there a total banning of the players?

Buck Weaver was banned not for dumping but for allegedly having guilty knowledge that there was a plot. Fred McMullen was banned, though he came to bat twice and got one hit. And Joe Jackson was banned, although his performance exceeded his own standards.

Most importantly, the eight players were found not guilty in a court of law. Yet, they were found guilty by a brand new baseball commissioner.

At the trial, Joe Jackson was asked under oath:

“Did you do anything to throw those games?”

“No sir,” was his response.

“Any game in the series?”

“Not a one,” was Jackson’s response. “I didn’t have an error or make no misplay.”

With the banning from baseball for life of “Shoeless Joe” Jackson and the seven other White Sox players, it seemed the sport was saying: “Now we are clean. Now we have purged ourselves of the dishonest ways of the past in the national pastime.” And if Jackson in the prime of his baseball career and the others were sacrificed, that was the way it had to be.

Shoeless Joe Jackson maintained that he had played all out in that World Series of 1919. Nevertheless, Major League Baseball was done with Jackson and his seven teammates. It was a miscarriage of justice, a field day for slander on parade. Powerless players were punished, scapegoated.

For a couple of decades, Jackson attempted to play the game that he loved, the game that he had learned so well back in the days of his youth. He made an effort to play with outlaw barnstormers, mill teams, semi-pro outfits. Aliases and disguises did him not much good; his unmistakable talent brought the spotlight to bear on him. Relentless, unforgiving, prejudiced Judge Landis, to keep Jackson from playing, threatened baseball team owners and league officials.

In 1932, Jackson applied for permission to manage a minor league team in his home town of Greenville, South Carolina. Landis denied the application.

In 1951, Joseph Jefferson Jackson died of a massive heart attack a week before he was to appear on the Ed Sullivan television show. He was scheduled to receive a trophy honoring him for being inducted into the Cleveland Indians Baseball Hall of Fame.

It is an old story.

The roster of Hall of Famers includes personalities with much shabbier credentials and far more soiled reputations. Attempts to get Joe Jackson into the Baseball Hall of Fame failed during and after his lifetime. Yet, Jackson’s shoes are at Cooperstown. Yet, his life-sized photograph is there. So is a baseball bat he used, along with the jersey he wore in the 1919 World Series. So is the last Major League Baseball contract he signed.

Prominent attorneys like Alan Dershowitz and F. Lee Bailey have argued that Jackson should go into the Hall. There have been petitions, Congressional motions, letters sent to baseball Commissioners through the years—all to no avail.

Commissioner Bart Giamatti said: “I do not wish to play God with history. The Jackson case is best left to historical debate and analysis. I am not for reinstatement.”

Commissioner Faye Vincent said, “I can’t uncipher or decipher what took place back then. I have no intention of taking formal action.”

Commissioner Bud Selig did not stand up for Joe Jackson even though he met with Ted Williams, who pushed for Jackson’s admission to the Hall of Fame.

Four times Jackson batted over .370. His lifetime batting average was .356, topped only by Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby. Ruth, Cobb, and Casey Stengel all placed him on their all time, All-Star team.

Joe Jackson was vilified through the decades by many who never knew or didn’t care to know the full story. His, however, is a story that just will not go away.

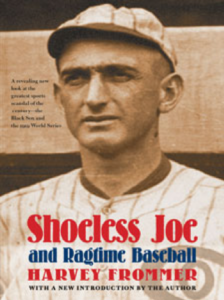

ABOUT HARVEY FROMMER

One of the most prolific and respected sports journalists and oral historians in the United States, author of the autobiographies of legends Nolan Ryan ,Tony Dorsett, and Red Holzman, Dr. Harvey Frommer, a professor for more than two decades in the MALS program at Dartmouth College, was dubbed “Dartmouth’s Mr. Baseball” by their alumni magazine. He’s also the founder of www.HarveyFrommerSports.com and has written extensively about Shoeless Joe Jackson. Signed, mint condition copies of his book on Jackson and other books can be obtained from his site.